In this weeks Mishpacha Magazine: Bring On The MUSIC – Daniel Ahaviel Unlikely Following

by yossi | May 9, 2012 7:35 am

In this weeks Mishpacha Magazine there is an amazing interview with world renown violinist Daniel Ahaviel. You can read part of the interview below.

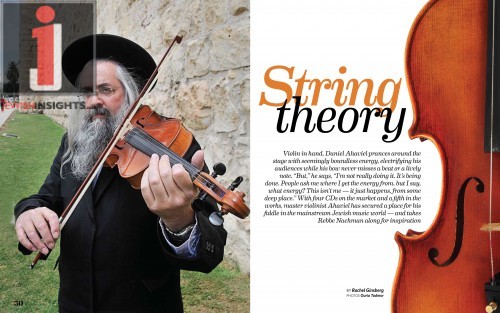

Violin in hand, Daniel Ahaviel prances around the stage with seemingly boundless energy, electrifying his audiences while his bow never misses a beat or a lively note. “But,” he says, “I’m not really doing it. It’s being done. People ask me where I get the energy from, but I say, what energy? This isn’t me — it just happens, from some deep place.” With four CDs on the market and a fifth in the works, master violinist Ahaviel has secured a place for his fiddle in the mainstream Jewish music world — and takes Rebbe Nachman along for inspiration

by Rachel Ginsberg

photos Ouria Tadmor

There’s a certain energy exuded by a master artist that draws people, even if they don’t know who he is. When Daniel Ahaviel was fiddling outside Jaffa Gate for our photo shoot, passersby just knew they were witnessing something extraordinary, and joined our photographer Ouria, taking out their smartphones to capture their own photos of this chassidic-garbed violinist playing to his heart’s content against the Old City walls. One woman insisted on throwing a handful of change into his violin case. “Oh, please take this,” she implored, generously trying to donate 50 agurot (about 15 cents) to him.

Daniel smiled graciously. A lifetime ago, he was happy to play on the streets of Europe with his case open, waiting for change. Well, the change came, but not the coin variety. Instead, it was what he calls the emergence of his essence — the transformation from a secular music graduate trying to find a niche for himself to a Breslover chassid electrifying his audiences with the musical energy that comes from the depths of the neshamah.

“When I was growing up, my entire connection to Judaism was that it was simply a relic of the past,” Daniel Ahaviel tries to put his background into perspective. He was born in northwest London 48 years ago as Daniel Wistrich, to left-wing, idealistic, forward-thinking parents who had exchanged all vestiges of their Judaism for a commitment to a progressive England and a united Europe. His father, Ernest Wistrich — originally Wistreich, son of a well-off, assimilated family in prewar Poland — managed to get on the last train out before the Nazi invasion.

He quickly acclimated to the surrounding English culture and Anglicized his name. As an accomplished social activist, he lobbied for Britain to join the European Union and for the creation of the euro currency. Daniel’s mother is a retired academic and local Labour councillor.

“I knew nothing about Judaism except that Jews died in the Holocaust,” Daniel says. The family didn’t go to shul on Yom Kippur, and he didn’t have a bar mitzvah. “Three-quarters of my family on both

sides perished in Poland, and I grew up thinking Judaism as a relevant spiritual force was dead.”

Daniel’s musical talent developed almost accidentally, and under unfortunate circumstances. His mentally disabled older brother — who passed away as a teenager — was sent to a music therapist, and

little Daniel was his escort. Daniel was enchanted by the music, and the teacher encouraged his parents to develop his talents. She even predicted he would one day become a great concert violinist.

Daniel began playing violin and piano at age eight, spent his teenage years studying with some of the most talented young musicians in London, and then decided to study for a music degree at the University of York — unaware of the ancient rabbinic tradition of a 12th-century cherem forbidding Jews to sleep in York overnight following the infamous York massacre of 1190.

Twelfth-century York contained one of the largest Jewish communities in England at the time, serving as a center of Jewish scholarship. All that came to an end in the years 1189–1190, when murderous rioters took to the streets after Richard the Lionheart ascended the throne and announced his dedication to the Crusades. The York massacre was the climax of a tide of murderous violence that swept the country when Crusaders incited local mobs to pillage and massacre whole Jewish communities. On Shabbos HaGadol, 1190, the madness reached York. About 150 Jews who took refuge in Clifford’s Tower from the enraged mob chose to die at each other’s hands rather than succumb to baptism. And the Jews who did surrender were immediately killed.

Daniel’s grandmother was appalled to hear that he was planning on going to York. “They kill Jews there, you know,” she commented sagely. “Granny,” he reassured her, “that was 800 years ago.”

But the circle actually closed eight centuries later, in the summer of 1984. Soon after Daniel performed with the university orchestra in York Minster cathedral, the ancient wing of the structure — which dated back to the time of the York massacre — mysteriously burned down in a freak summer night lightning storm. Many observers attributed the lightning to a divine act of retribution. The very day before the strike, bones from ancient Jewish cemeteries that had been dug up and desecrated during the building of a shopping center were, after months of intrigue and negotiations, finally reinterred in a halachically appropriate manner — and researchers believe many of those bones were remains of the York martyrs.

Daniel remembers watching that spectacular lightning storm in York the night of the fire, but it was only years later, once he was living in Israel and living a Torah lifestyle, that he heard the full story of the events leading up to the dramatic finale of an 800-year-old saga…

[1]

[1]

To read the rest of the article please visit your newsstands to pick up this weeks issue of Mishpacha Magazine or visit Mishpacha.com.

- [Image]: http://www.thejewishinsights.com/wp/weeks-mishpacha-magazine-bring-music-daniel-ahaviel/daniel-ahaviel-1/

Source URL: https://www.thejewishinsights.com/wp/weeks-mishpacha-magazine-bring-music-daniel-ahaviel/